Chapter 28Sharing the Quaker experience |

|

28.01 |

The very simple heart of the early Quaker message is needed as much to-day as it ever was… The really universal thing is a living experience. It is reached in various ways, and expressed in very different language… The common bond is in the thing itself, the actual inner knowledge of the grace of God. Quakerism can only have a universal message if it brings men and women into this transforming knowledge. The early Friends certainly had this knowledge, and were the means of bringing many thousands of seekers into the way of discovery. In virtue of this central experience, the Quaker movement can only be true to itself by being a missionary movement. Henry T Hodgkin, 1916 |

28.02 |

When you come to your meetings … what do you do? Do you then gather together bodily only, and kindle a fire, compassing yourselves with the sparks of your own kindling, and so please yourself … ? Or rather do you sit down in the true silence, resting from your own will and workings, and waiting upon the Lord, with your minds fixed in that Light wherewith Christ has enlightened you … and prepares you, and your spirits and souls, to make you fit for his service? William Penn, 1677 |

28.03 |

Now I was sent to turn people from darkness to the light that they might receive Christ Jesus, for to as many as should receive him in his light, I saw that he would give power to become Sons of God, which I had obtained by receiving Christ. And I was to direct people to the Spirit that gave forth the Scriptures, by which they might be led into all Truth, and so up to Christ and God, as they had been who gave them forth. And I was to turn them to the grace of God, and to the Truth in the heart, which came by Jesus, that by this grace they might be taught, which would bring them into salvation, that their hearts might be established by it, and their words might be seasoned, and all might come to know their salvation nigh. George Fox, 1648 |

28.04 |

When I grew to about thirteen years of age, I began to discover something about me, or in my mind, like the heavenly anointing for the ministry; for the Lord had revealed His word as a hammer and had broken the rock in pieces in my living experience; and I was contrited under a sense of power and love; saying even vocally when alone, ‘Lord, make me a chosen vessel unto Thee’… With respect to my first appearances [in ministry, when about seventeen years old]… I shrunk from it exceedingly; and often have I hesitated, and felt such a reluctance to it, that I have suffered the meeting to break up without my having made the sacrifice: yea, when the word of life in a few words was like a fire within me… It pleased the Lord to call me into a path much untrodden, in my early travels as a messenger of the Gospel, having to go into markets and to declare the truth in the streets… No one knows the depth of my sufferings and the mortifying, yea, crucifying of my own will, which I had to endure in this service; yet I have to acknowledge to the sufficiency of divine grace herein… At Bath I had to go to the Pump Room and declare the truth to the gay people who resorted there. This was a time very relieving to my sorely exercised mind. In these days and years of my life I was seldom from under some heavy burden, so that I went greatly bowed down; sometimes ready to say, ‘If it be thus with me, O Thou who hast given me a being, I pray Thee take away my life from me’… In the year 1801, I wrote thus: ‘O heavenly Father, Thou hast seen me in the depth of tribulation, in my many journeyings and travels… It was Thy power which supported me when no flesh could help, when man could not comprehend the depth of mine exercise… Be Thou only and for ever exalted in, by and through Thy poor child, and let nothing be able to pluck me out of Thy hand.’ Sarah Lynes Grubb, 1832 See also 2.55 |

28.05 |

An apprehension has seized upon my mind this morning, that after having finished the little books I am preparing for the children of Sierra Leone, it will be my duty to attempt the introduction of them myself into that country and the neighbourhood, and even to attempt the reduction of unwritten languages. I would not go merely under a profession of opening a school or schools, but to proceed to the religious instruction of the children, for my heart feels an engagement towards them that cannot possibly be fulfilled without going there. Hannah Kilham, 1817 |

28.06 |

Jesus saw the truth that men needed and he thought it urgent that that truth should be proclaimed. That trust is handed on to us, but it is a responsibility from which we shrink. We feel that we have a very imperfect grasp of the meaning of the Gospel. Perhaps, after all the earnest seeking of the Church, we are only beginning to see the tremendous implications of it. We dimly see that this Gospel, before it has finished with us, will turn our lives upside down and inside out. Our favourite Quaker vice of caution holds us back. We have much more to learn before we are ready to teach. It is right that we have much to learn; it is right to recognise the heavy responsibility of teaching; but to suppose that we must know everything before we can teach anything is to condemn ourselves to perpetual futility. George B Jeffery, 1934 |

28.07 |

‘Have you anything to declare?’ is a vital challenge to which every one of us is personally called to respond and is also a challenge that every meeting should consider of primary importance. It should lead us to define, with such clarity as we can reach, precisely what it is that Friends of this generation have to say that is not, as we believe, being said effectively by others. Edgar G Dunstan, 1956 |

28.08 |

We live in a rationalist society that has shed the security of dogmas it found it could not accept, and now finds itself afraid of its own freedom. Some look for an external authority, as they did of old; but in this situation there are many who cannot just go backwards. They ask for an authority they can accept without the loss of their own integrity: they ask to be talked to in a language they can understand… With these people our point of departure is not a mighty proclamation of Truth, but the humble invitation to sit down together and share what we have found, in the spirit of Woolman setting out on his Indian journey, ‘that I might feel and understand their life, and the spirit they live in, if haply I might receive some instruction from them.’ We approach them without pressure to accept a statement, or with proselytising zeal, but with ‘love as the first motion’. Harold Loukes, 1955 27.02 gives a fuller version of John Woolman’s account |

28.09 |

Outreach is for me an invitation to others to join us in our way of worship and response to life which are so important to us that we wish to share them. At the simplest level this means supplying information about meetings, Friends to contact, and basic beliefs, all of which should be given accurately, clearly and if possible attractively. In the second stage outreach offers to others, through meetings, personal contact and literature, the experience and truth which Friends have found for themselves through three centuries and which impel us just as strongly today. It is different from some forms of evangelism in that it does not use mass emotional appeal, idiosyncratic demands or autocratic compulsion but only the persuasion of insight, humanity and good sense. It does not depend on rewards or threats, but on the active acceptance of those who see it as truth. Edrey Allott, 1990 |

28.10 |

Many of the people who come to us are both refugees and seekers. They are looking for a space to find their authenticity, a space in a spiritual context. It is a process of liberation. Some discover what they need among Friends, others go elsewhere. This gift of the sacred space that Friends have to offer is a two-edged sword. It is not easy administratively to quantify; it leads to ambiguity. It demands patient listening; it can be enriching and challenging to our complacency. It is outreach in the most general sense and it is a profound service. It may not lead to membership and it may cause difficulties in local meetings. But if someone comes asking for bread, we cannot say, sorry we are too busy discovering our own riches; when we have found them, we’ll offer you a few. Our riches are precisely our sharing. And the world is very, very hungry. Harvey Gillman, 1993 |

28.11 |

Only such writings as spring from a living experience will reach the life in others, only those which embody genuine thought in clear and effective form will minister to the needs of the human mind. A faith like Quakerism should find expression in creative writing born of imagination and spirit, and speaking in universal tones that will be understood by many who fail to understand the common presentations of Christianity. It is no disrespect to truth to present it in forms that will be readily understood. 1925 |

28.12 |

Sharing the Quaker message today does not mean sharing it [only] in English. It means carrying it in French, from Burundi Yearly Meeting to Madagascar. Or standing in Kenya, telling of your faith as a Bolivian Friend in Aymara to be translated into Spanish and then into English and then whispered into Luragoli for the old Friend in the back row! Those who carry the Quaker message today are not only those who worry about whether sanctions against South Africa are right or wrong. Quakers today are the victims of violence and racism in Soweto. Quakers today are not simply watching pictures of famine on their televisions; they are farming the inhospitable altiplano in Bolivia; they are facing drought in Turkana. Val Ferguson, 1987 |

28.13 |

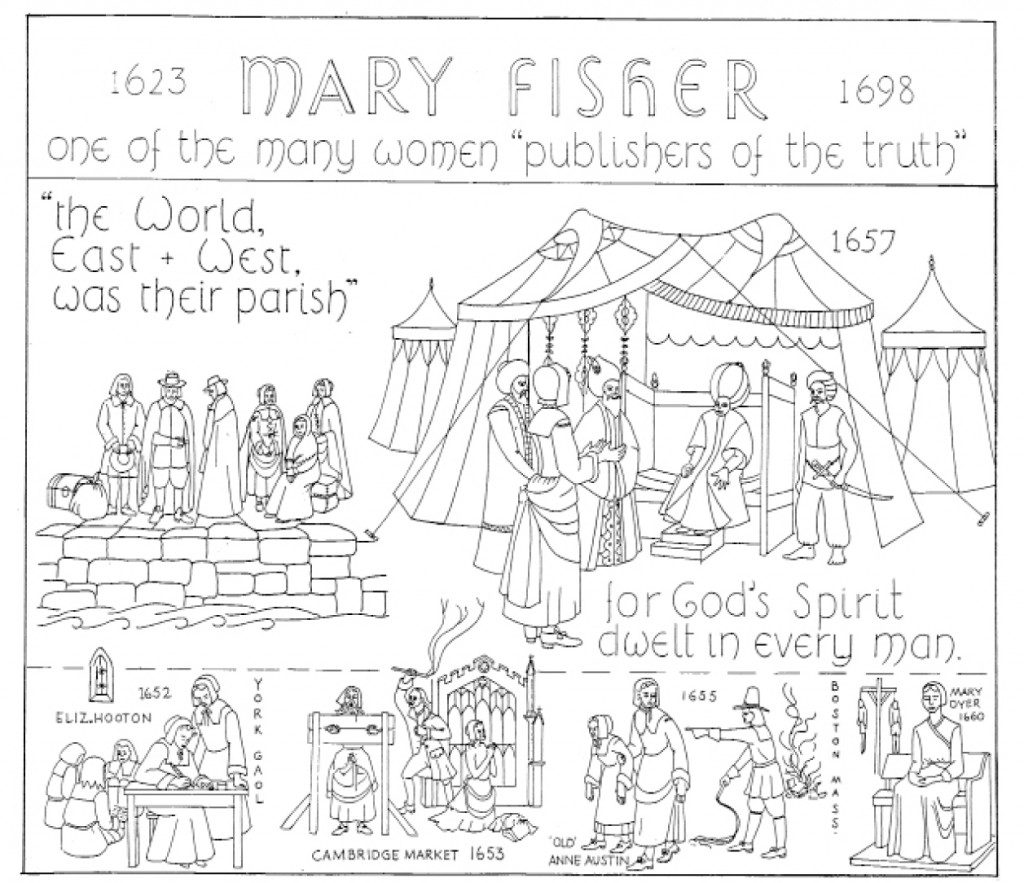

The Quaker Tapestry is a series of over seventy embroidered panels illustrating the history and experiences of Friends. It sprang from an idea in a children’s class in a Somerset meeting in 1981, and has been made by many hands in many meetings. It is a new way of sharing Quaker insights through exhibitions in Britain, Ireland and other countries. It is now on permanent exhibition at Kendal Meeting House. The following line drawing is a reproduction of one of the cartoons used to plan the tapestry panels.

© Quaker Tapestry Scheme This panel, Mary Fisher, illustrates the work of the ‘first publishers of truth’, as the first Friends who left home to witness to the Light were called. (For an extract from the writing of Mary Fisher, see 19.27.) Our book of discipline tells how Friends try to live by the leadings disclosed in worship and prayer. The early Friends believed that they had rediscovered true Christianity and that they had a duty to tell the world. They travelled widely, ‘publishing the truth’, first throughout Britain and then overseas, even approaching the sultan of Turkey. Now, however, most of the journeys from Britain Yearly Meeting are to do service work: teaching, reconciling, helping with development. There are many small groups of Friends who owe their origin to the spirit reflected in those doing such work, who ‘let their lives speak’. Evangelical meetings in some parts of the world lay great emphasis on missionary work, as British and Irish Friends did in the past, and as a result there are many thousands of Friends of the programmed tradition in countries such as Kenya and Bolivia. It is part of our service to try to communicate the faith that we have tested in experience. We long to reach out to those who may find a spiritual home in the Society; we do not claim that ours is the only true way, yet we have a perception of truth that is relevant to all if, as we believe, the light to which we witness is a universal light. Each meeting must find its own way of sharing the Quaker experience, each Friend remember ‘that we are each the epistle of Yearly Meeting’. |

Table of Contents

Reading Qf&p

The Book of Discipline Revision Preparation Group invites you to join with us, and other Quakers across the country, in reading and getting to know our current Book of Discipline.